During the reign of Emperor Dụ Tông, the Trần dynasty fell into a severe crisis. The heroic spirit of Đông A was no longer present. The internal contradictions of the manor and fiefdom system deepened.

The Trần aristocracy increasingly degenerated, indulging in luxurious lives. Serfs and slaves, subjected to brutal oppression and exploitation, rose in rebellion. Natural disasters struck repeatedly, halting production and leaving the people impoverished. Meanwhile, the southern kingdom of Champa raided the borders year after year. The royal court was in decay, the emperor was incompetent, eunuchs wielded unchecked power, and virtuous individuals distanced themselves from the court. The Trần dynasty faced imminent collapse despite the efforts of many distinguished Confucian scholars to stabilize the situation. However, they were ultimately powerless against the inevitable decline.

Following the Dương Nhật Lễ incident, Emperor Trần Nghệ Tông managed to reclaim the throne. However, facing a crumbling monarchy, he had to find a suitable policy to stabilize the nation. Trained in the philosophy of Song Confucianism, Nghệ Hoàng was sympathetic to rigid Confucian scholars, but their ideals were insufficient to restore the Trần dynasty.

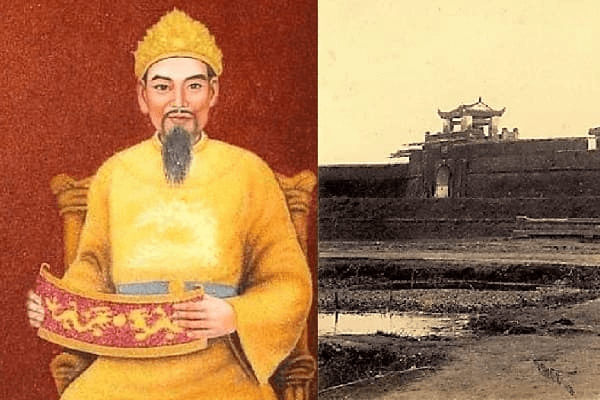

Times had changed, demanding a different approach and a leader distinct from the typical Song Confucian model to reverse the situation. Nghệ Hoàng saw in Hồ Quý Ly a new Tô Hiến Thành, capable of revitalizing the Trần dynasty. The phrase embroidered on the banner bestowed upon Quý Ly—“A master of both civil and military affairs, sharing virtue with the ruler”—reflected this recognition.

Hồ Quý Ly ascended to military power partly through his familial ties to the Trần dynasty. However, Nghệ Hoàng’s trust in him stemmed not only from these ties but also from Quý Ly’s compelling political ideology and dynamic leadership style. Trần Nghệ Tông, a gentle and benevolent but weak and passive ruler, bore the heavy responsibility of restoring the Trần dynasty. In contrast, Quý Ly was sharp, resourceful, decisive, and energetic—qualities that made him a valuable ally in shouldering this burden. Nghệ Hoàng’s disappointment with the conservative, ineffective Confucian scholars further strengthened his reliance on Quý Ly, leading him to entrust Quý Ly with significant responsibilities. Additionally, the court’s internal politics played a role, as Nghệ Hoàng’s mother and Emperor Duệ Tông were both Quý Ly’s aunts, and Princess Huy Ninh was his wife.

So why did Nghệ Hoàng favor Quý Ly? The answer lies in Quý Ly’s political vision and governing approach, as demonstrated through his words, writings, and actions.

It is a mistake to assume that Quý Ly was merely a military man with little education. Throughout his decades of service to the Trần dynasty and his subsequent reign, his speeches, writings, and policies reveal a deep intellectual foundation. He was well-versed in the Classics, Hundred Schools of Thought, and Three Teachings and Nine Streams. His profound knowledge enabled him to boldly write Minh Đạo, reorganize the hierarchy of sages, challenge The Analects, compose Thi Nghĩa in the vernacular language, and translate Thiên vô dật, all with the purpose of fiercely criticizing Song Confucianism. Clearly, Quý Ly was an exceptional scholar. Not only did he persuade Nghệ Hoàng, but he also won the support of numerous progressive intellectuals of his time, such as Hoàng Hối Khanh, Đỗ Tử Trừng, Nguyễn Phi Khanh, Vũ Mộng Nguyên, and Nguyễn Trãi. They rallied around him to partake in his reform efforts.

Hồ Quý Ly’s Governance and Leadership Style

First, Quý Ly rejected the purely moral-based governance of conservative Confucians like Cheng-Zhu scholars, who clung to outdated doctrines of virtue and ethics. The golden ages of Nguyên Phong and Long Hưng were over. As he assumed power during a period of decline and chaos, Quý Ly strongly advocated for Legalist governance, placing law and order at the core. He used autocratic measures to enforce absolute obedience, implementing harsh punishments to suppress opposition and executing economic, political, military, and cultural reforms with an iron fist.

This authoritarian legalist approach aligned with Trần Nghệ Tông’s concerns about the monarchy’s weakening authority. Consequently, Nghệ Hoàng endorsed these policies, lending his name to their implementation—a path later pursued even more aggressively by Emperor Hán Thương. Only Hồ Nguyên Trừng foresaw the inevitable failure of such extreme measures, but lacking Quý Ly’s trust, he did not dare to intervene.

Hồ Quý Ly’s policies were consistent throughout his career. His reforms were not implemented all at once but gradually, beginning with his appointment as Khu Mật Đại Sứ (Head of the Secret Council), progressing to the title of Đại Vương Quốc Tổ Chương Hoàng, and ultimately becoming emperor. Naturally, once he consolidated power, his reforms were enacted with full force. These changes encompassed various aspects of society, economy, politics, military affairs, foreign policy, and culture.

Regardless of Hồ Quý Ly’s personal motivations and ethical considerations, his reforms addressed many pressing issues of late 14th-century Đại Việt. The existing feudal system of large estates and decentralized rule could no longer sustain societal progress. Economic and social development required transferring land ownership to private individuals and liberating serfs and slaves to stimulate production. Financial and monetary reforms were essential for national expenditure and trade. The political structure demanded a strong centralized government with an effective bureaucracy, a formidable military, and a national culture independent of Chinese influence. Despite their limitations, Hồ Quý Ly’s reforms reflected progressive ideals grounded in the realities of the time. If executed wisely, they could have strengthened the nation. Later, Lê Lợi and his successors built upon lessons learned from the Hồ era to rejuvenate Đại Việt.

Why Did Hồ Quý Ly’s Reforms Fail?

Despite being aligned with historical necessity, Hồ Quý Ly’s reforms ultimately led to the downfall of the Hồ dynasty and earned severe condemnation from history.

- Excessive Legalism and Harsh Rule

While virtue-based governance was no longer suitable for a chaotic society, Quý Ly’s extreme reliance on legalist policies led to brutality. He enforced reforms through coercion, forcibly relocating the capital, and constructing Tây Đô against widespread opposition. By entirely discarding the humane governance traditions of the Trần dynasty, he alienated the populace. - Lack of Popular Support

Though aimed at national strength, his reforms did not genuinely prioritize the well-being of the working class and middle strata. His failure to recognize that “the people are like water; they can float a boat or overturn it” led to widespread discontent. - Dynastic Interests Over National Interests

Quý Ly’s reforms never transcended feudal ideology. As a minister, he served the Trần dynasty; as an emperor, he prioritized the Hồ family’s power. His national strengthening efforts were ultimately driven by dynastic ambitions. - Acquiring Power Through Manipulation Rather Than Merit

Quý Ly’s rise was not based on moral authority but on political maneuvering. He built a factional power base and ruthlessly eliminated opposition, earning public resentment. - Incomplete and Rushed Reforms

His half-measures antagonized conservatives while failing to fully satisfy reformists. Furthermore, he lacked time to solidify his changes. As a Trần minister, he hesitated to act decisively; as emperor, he faced both internal resistance and external threats from Champa and Ming China.

With a weak political foundation, the Hồ dynasty was doomed when faced with the mighty Ming invasion. Quý Ly failed to defend the nation and was captured along with his son, becoming a prisoner of the Ming—a humiliation the Vietnamese people never forgot. In contrast, figures like Lê Hoàn, Lý Công Uẩn, and Trần Thủ Độ also usurped power but were not condemned because they successfully defended and strengthened the nation.

The lesson from Hồ Quý Ly’s reforms is that governance must adapt to social realities, balancing virtue and law. A ruler must win the people’s trust while enforcing discipline. Only through such harmony can a nation achieve sustainable strength and prosperity.