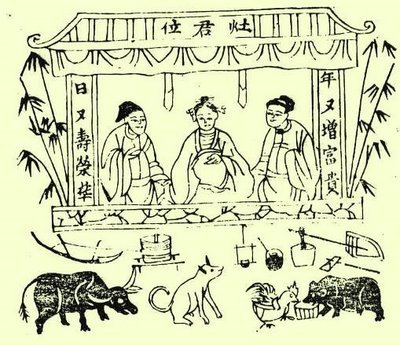

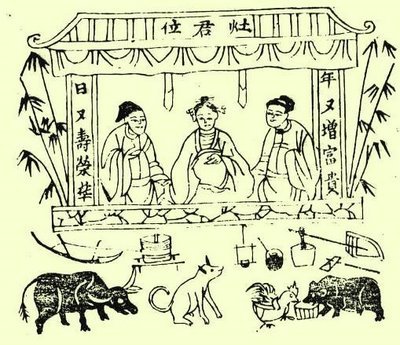

The tradition of Ông Táo, also known as the Kitchen Gods or Táo Quân, is an integral part of Vietnamese culture and religious practice, especially observed during the Tết Nguyên Đán, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year. Rooted in ancient Taoist beliefs, Ông Táo are regarded as the protectors of the household and the guardians of the family’s kitchen. This custom reflects the Vietnamese people’s reverence for their home and the pivotal role the kitchen plays in daily life.

Artist: Đoàn Thành Lộc.

Origins and Legend

The legend of Ông Táo originates from a folk tale about a couple and a stranger who become entwined in a tragic yet mystical story. According to the tale, a woman, after separating from her husband due to poverty, remarries. Later, her first husband, now a beggar, unknowingly seeks shelter at her new home. Recognizing him, the woman attempts to help him secretly, but her new husband discovers the situation. In a desperate effort to save her former spouse from harm, the woman sacrifices herself in a fire. Moved by their loyalty and love, the Jade Emperor appoints the three as the Kitchen Gods, symbolizing fidelity and familial harmony.

Roles and Significance

In Vietnamese households, Ông Táo consists of three deities: two male gods and one female goddess. They are believed to reside in the kitchen, monitoring the family’s affairs and maintaining the household’s well-being. The Kitchen Gods are responsible for reporting the family’s activities to the Jade Emperor annually. This report influences the family’s fortune and luck for the coming year.

Annual Rituals

The ritual of honoring Ông Táo occurs on the 23rd day of the last lunar month, known as Tết Táo Quân or Ông Công Ông Táo. On this day, families perform a ceremonial farewell to the Kitchen Gods, who depart to the heavens to deliver their report. The farewell ceremony includes various offerings:

1. Carp Fish: In many regions, live carp fish are released into rivers or ponds as they are believed to serve as the Kitchen Gods’ transportation to the heavens.

2. Paper Offerings: Paper effigies of the Kitchen Gods and their clothing are burned as symbolic offerings.

3. Food and Incense: Traditional foods, fruits, sweets, and incense are offered at the household altar.

This ceremony not only reflects gratitude but also serves to cleanse the household and prepare for a prosperous new year.

Modern Adaptations

While traditional practices remain prevalent, modern adaptations have emerged. In urban settings, the use of symbolic paper offerings often replaces the release of live fish. Some families also incorporate additional contemporary elements, such as electronic candles or digital prayers, reflecting a blend of tradition and modernity.

Modern adaptations of Ông Táo (the Kitchen Gods) in the Táo Quân show have transformed these traditional deities into a satirical and comedic lens on contemporary Vietnamese society. Instead of merely focusing on their mythological role of reporting to the Jade Emperor, the Táo Quân characters are reimagined as commentators on pressing social issues, from education reform to economic trends and cultural shifts. Through witty dialogue and theatrical performances, the show uses humor and allegory to reflect the public’s concerns and aspirations. This modernization has revitalized interest in the tradition, blending ancient beliefs with modern storytelling, and keeping the spirit of Táo Quân alive in an engaging and relatable way for today’s audiences.

Conclusion

The tradition of Ông Táo underscores the importance of the kitchen and the household in Vietnamese culture. By honoring the Kitchen Gods, Vietnamese families express their respect for home, family harmony, and the cyclical renewal of life. This enduring practice not only preserves cultural heritage but also reinforces communal values and spiritual beliefs, ensuring that the legacy of Ông Táo continues to thrive in modern Vietnam.