Trường Tiền bridge (Hue City), designed by the renowned French engineer Gustave Eiffel, carries a truly turbulent fate. Built to connect the two banks of the Perfume River, separating the Southern Court (on the north bank) from the French protectorate government (on the south bank), it only intensified the tensions between France and Vietnam.

Three times the bridge collapsed due to natural disasters and wars. Four times it was renamed. Even the names it bore reflect the ebb and flow of history.

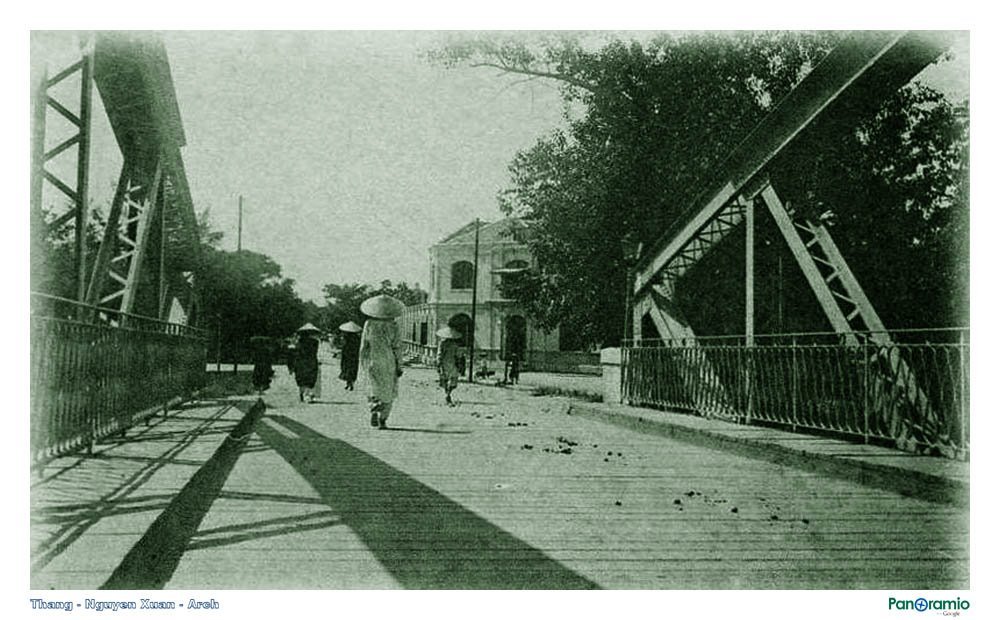

Thành Thái Bridge and the Pain of Enslavement

Trường Tiền Bridge was born with the imprints of two key figures in late 19th to early 20th-century Vietnamese history: Emperor Thành Thái and Paul Doumer, Governor-General of French Indochina.

Paul Doumer personally named the bridge “Thành Thái Bridge” after the emperor, acknowledging his role in initiating its construction, which began with an imperial edict in September 1896:

“The most important aspect of virtuous governance is granting grace to the people. Recently, undertaking the construction of roads and bridges has been to the people’s benefit. Now, following the suggestion of the Privy Council, I believe a steel bridge should be built for convenience in travel.”

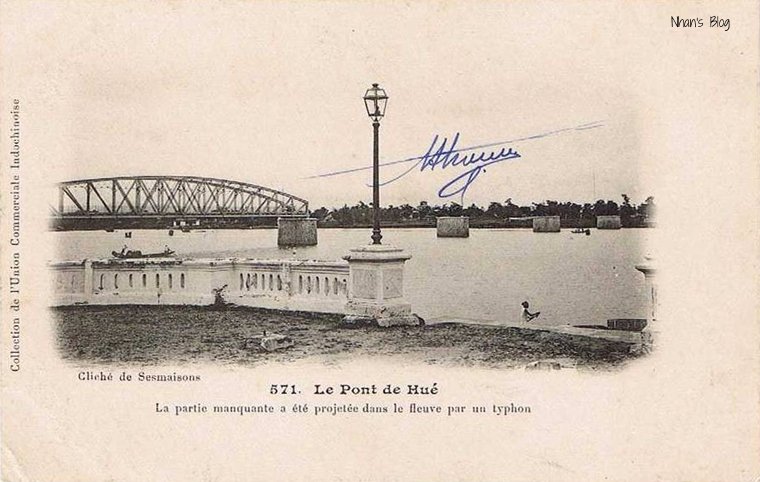

Governor-General Doumer proposed building a spacious and durable bridge, with additional costs covered by the protectorate government. In October 1900, Emperor Thành Thái and Doumer jointly inaugurated the steel bridge over the Perfume River.

Ascending the throne at the age of 10 in 1889, Emperor Thành Thái was 21 years old when the bridge was completed in 1900. Historical documents from the Nguyễn Dynasty reveal that Thành Thái opposed French colonial rule but was not xenophobic. He had progressive ideas and actively studied Western technologies. He planned reforms to modernize Vietnam, but his initiatives were consistently blocked by French officials.

When the Giáp Thìn typhoon of 1904 swept away four spans of the Thành Thái Bridge, the emperor expressed his grief through a palindrome poem, which could be read both forwards and backwards:

“The old tiles replaced atop the high halls / The iron bridge here arches its bent back / The bent back arches again this iron bridge / The high halls atop the old tiles replaced.”

This lament reflected the emperor’s anguish over the loss of sovereignty and his court’s helplessness against foreign domination. The escalating conflicts led to his increasing despondency and defiance. In July 1907, the French deemed him insane and forced him to abdicate.

In November 1916, Thành Thái was exiled to Réunion Island in Africa along with his son, Emperor Duy Tân, who had also been deposed by the French. However, the bridge retained his name for another three years.

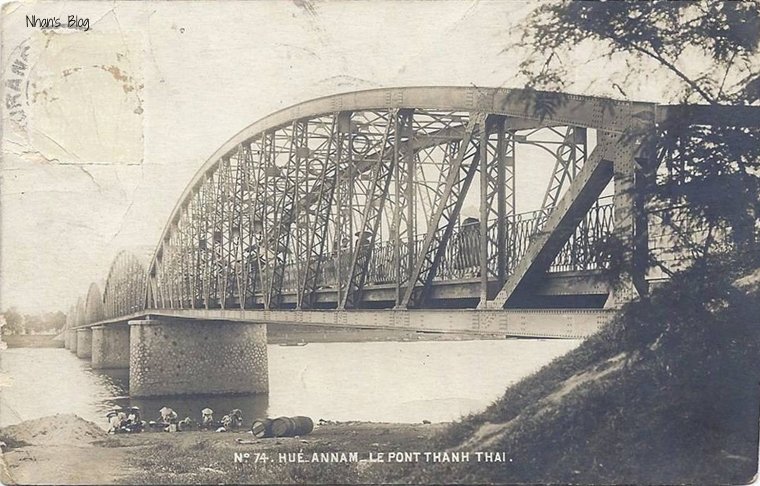

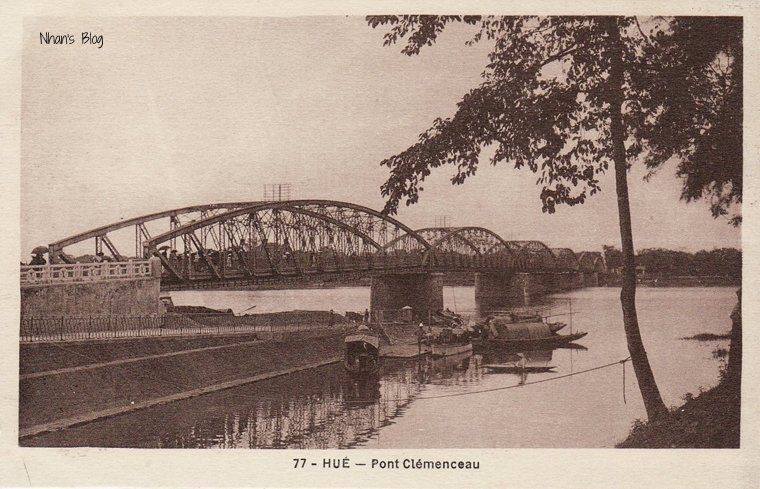

Clémenceau Bridge – A Foreign Name

In July 1919, Acting Governor-General M.A.F. Montguillot issued a decree renaming the “Hue Bridge.” From July 14, 1919, Thành Thái Bridge was officially renamed Clemenceau Bridge.

This decree was printed in the Bulletin administratif de l’Annam of 1919. At the time, Emperor Khải Định, Thành Thái’s successor, had just ascended the throne in April 1916 after Emperor Duy Tân’s deposition for anti-French activities.

Clemenceau was the name of the French Prime Minister during that period. Georges Clemenceau served as France’s Prime Minister from 1906 to 1909 and from 1917 to 1920. In Europe, Clemenceau was celebrated for leading France to victory in World War I, which ended in November 1918. However, in Hue, the local population had no idea who Clemenceau was.

In 1954, as the French withdrew from Indochina following the Geneva Accords, the name Clemenceau Bridge faded into the past.

Nguyễn Hoàng Bridge – A Mark of Liberation

Few people in Hue know that Trường Tiền Bridge once bore the name Nguyễn Hoàng Bridge, after the first Nguyễn lord who established control over the southern region of Vietnam.

The name Clemenceau Bridge was replaced with Nguyễn Hoàng Bridge in May 1945, as part of the movement to “erase Western names” following Japan’s coup against the French across Indochina.

According to researcher Dương Phước Thu, after Japan’s coup, Emperor Bảo Đại established a new cabinet under Prime Minister Trần Trọng Kim on April 17, 1945. A month later, in May 1945, the cabinet submitted a decree to Emperor Bảo Đại to reorganize administrative activities, which included replacing French names for streets, schools, and parks with Vietnamese ones.

Hue was the first city to implement this decree, renaming Clemenceau Bridge as Nguyễn Hoàng Bridge. In Vietnam 1945, American historian David Marr noted that the Trần Trọng Kim government’s actions were aimed at ending dependence on France.

However, the name Nguyễn Hoàng Bridge was seldom used. Subsequent documents and publications referred to the bridge as Trường Tiền Bridge, and the name eventually became the official one, though it’s unclear exactly when.

Trường Tiền Bridge – The Soul of the People

The name Trường Tiền predates the construction of the bridge. It refers to the “coin mint” established in 1775 by the Trịnh Lords after capturing Phú Xuân (present-day Hue). Located on the river’s left bank, near the Thượng Tứ Gate, the mint gave its name to the nearby ferry and, later, the bridge built there.

The name “Trường Tiền” is both memorable and rich with the sentiments of the Hue people.

In 1939, the bridge underwent a major renovation, which the Tràng An newspaper described as “the greatest architectural project ever undertaken by the protectorate government in Hue.” Yet, the paper, deemed pro-French, avoided calling it Clemenceau Bridge.

On July 4, 1939, the Tràng An newspaper wrote:

“Seeing that the bridge was built at Trường Tiền (…) it is called Trường Tiền Bridge, as it has always been, and few pay attention to its changing names. Unknowingly, this habit reflects a remarkably wise approach.”

The paper also offered a fair assessment:

“Whenever we set foot on this spacious and beautiful bridge, we should remember that it is a monumental achievement of the protectorate government, built with the sweat and tears of countless people.”

Trường Tiền Bridge During the 1968 Tet Offensive

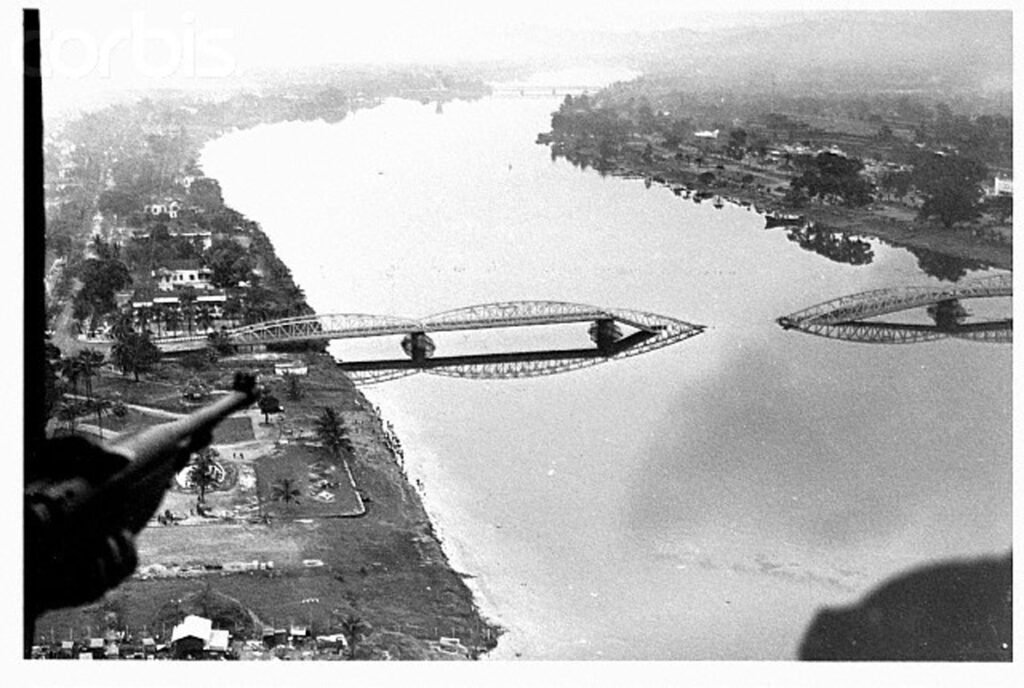

Trường Tiền Bridge became a battleground during the 1968 Tet Offensive, one of the most intense and pivotal events of the Vietnam War. As the bridge connected the two key sides of Hue City, its strategic location made it a focal point for both the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and the South Vietnamese forces, supported by the United States.

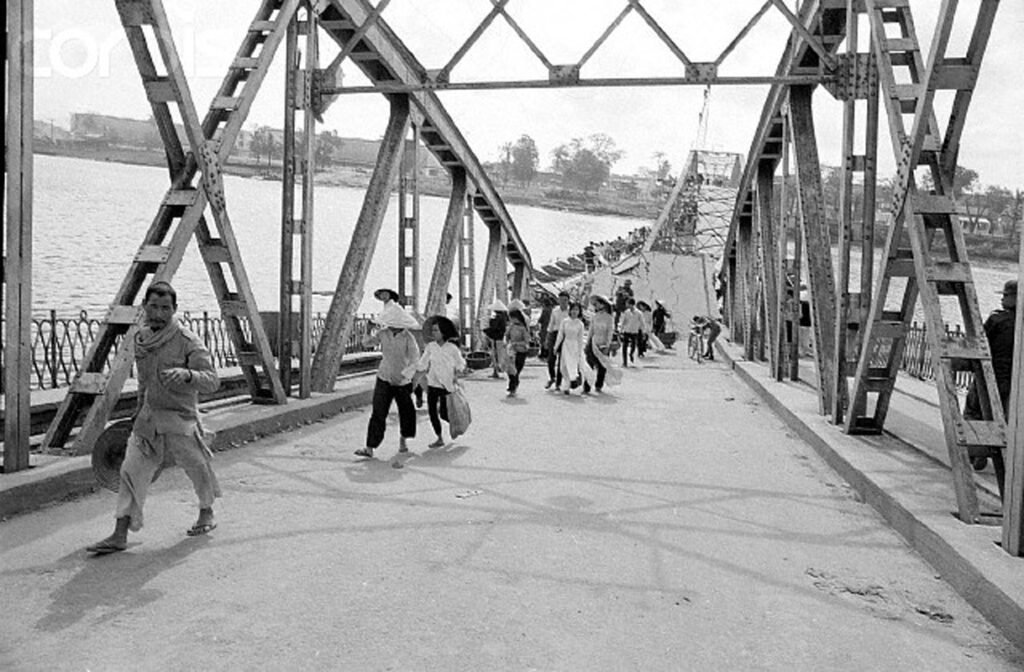

During the Tet Offensive, the NVA launched a coordinated assault on Hue, capturing most of the city, including the north bank of the Perfume River. Trường Tiền Bridge, however, was heavily contested, as it was a critical crossing for reinforcements and supplies. The South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) and U.S. forces fought to regain control of the bridge to reconnect the two banks and push the NVA out of the city.

The fighting around Trường Tiền Bridge was fierce, marked by artillery bombardments, airstrikes, and ground assaults. Parts of the bridge were severely damaged during the battle, with some spans collapsing due to the heavy shelling. The bridge became both a symbol of resilience and destruction, representing the broader devastation of Hue during the offensive.

Following the recapture of Hue by the ARVN and U.S. forces, the bridge was repaired, but the scars of war lingered. The events of 1968 further embedded Trường Tiền Bridge in the collective memory of the people of Hue, as it stood not only as a witness to the city’s historical shifts but also as a reminder of the suffering and resilience of its residents during one of the war’s most turbulent chapters.

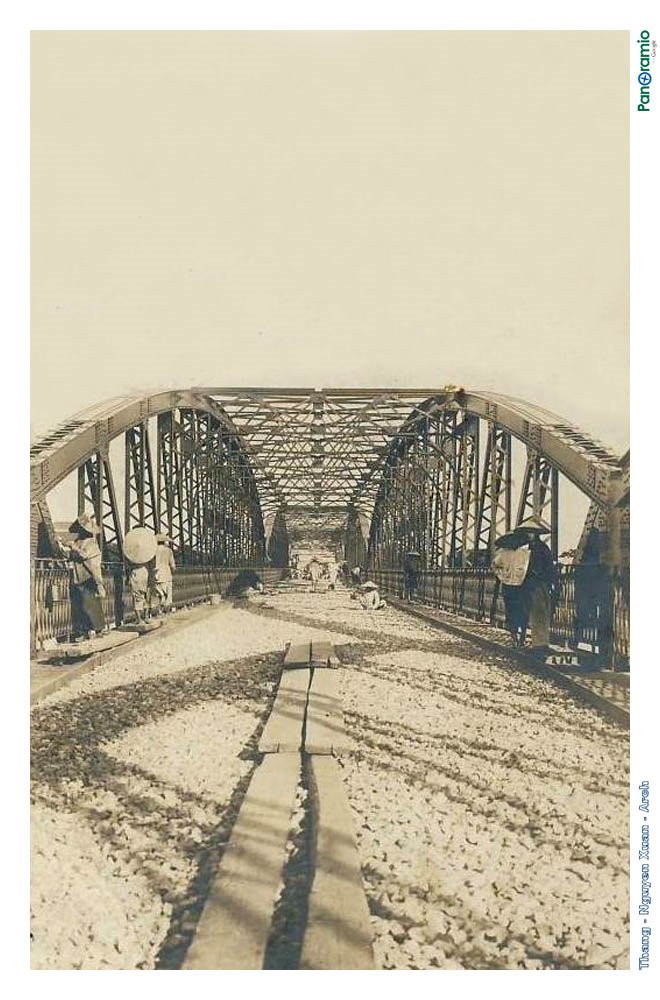

How Many Spans and Arches Does Trường Tiền Bridge Have?

The people of Hue and many historical records often claim that Trường Tiền Bridge has “six spans and twelve arches,” as referenced in a famous folk verse:

“Cầu Trường Tiền sáu vài, mười hai nhịp / Em qua không kịp tội lắm anh ơi!”

The Department of Transport of Thừa Thiên Hue states that the bridge consists of “six steel girder spans curved like comb teeth.” According to The Vietnamese Dictionary edited by Hoàng Phê, a bridge span is the distance between two piers or abutments. While the term “vài cầu” (translated as “spans”) is commonly used, it is likely a local variation of “vì cầu” or “vày cầu,” which refer to the structural connections supporting the bridge’s deck.

Based on these definitions, Trường Tiền Bridge has six spans, supported by five piers and two abutments, with two steel arches per span. Thus, the bridge technically has six spans and twelve arches.

Trường Tiền Bridge is more than just a physical structure connecting the banks of the Perfume River; it is a living testament to the tumultuous history of Hue and Vietnam as a whole. From its inception during the reign of Emperor Thành Thái to its renaming and reconstruction under French colonial rule, through the resilience it showed during natural disasters and wars, the bridge has borne witness to countless moments of transformation. Its various names and identities reflect the struggles and aspirations of the Vietnamese people, while its enduring presence symbolizes their resilience and capacity to rebuild. Today, Trường Tiền Bridge stands as an iconic symbol of Hue, carrying with it the weight of history and the hopes of generations to come.